Religious Iconography in Johnny Quintanilla’s Art

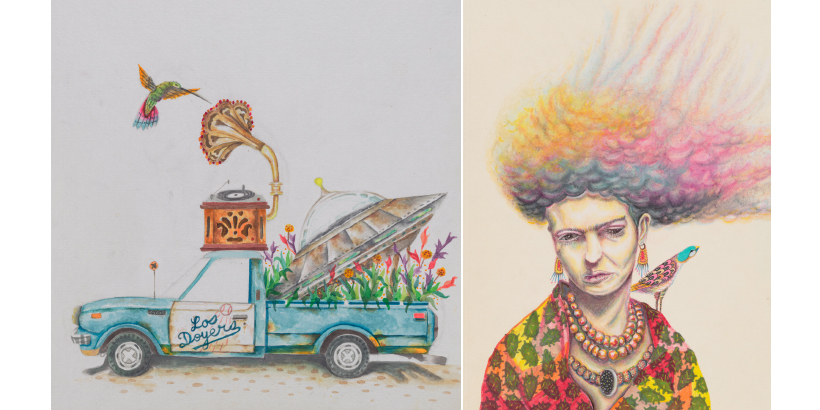

Last month, Pepperdine Libraries opened its exhibition of Johnny Quintanilla’s paintings and drawings in the Payson Library Exhibit Gallery. When I met with Quintanilla in the fall, he was excited to describe the meanings behind each piece and the symbolism depicted in his colorful compositions. Even though he reiterated that he likes when viewers form their own meanings about the works, it’s clear to me that for him they’re deeply personal. As I went through his portfolio, he shared stories of family and friends and how these experiences ended up in his work. His identity as a Salvadoran American who celebrates Los Angeles’ Latino heritage is also evident. Among other clues seen in his exhibited works, viewers will see a truck with the “Los Doyers” moniker, a portrait of the influential artist Frida Kahlo, and Central American-style clothing.

Another scene found in his work is the depiction of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The image typically features Mary, mother of Jesus, covered in a blue robe with her hands folded in prayer. Behind her, the sun – blocked by Mary’s body – emits cosmic rays of light, illustriously showing her divinity. The episode behind the image dates back to December 1531 in New Spain (now Mexico), when a recently converted Nahua man named Juan Diego began to see apparitions of the Virgin. The first of four encounters happened when he was on his way to the Franciscan house in Tlatelolco (in present-day Mexico City), the center of Catholic religious life in New Spain. As he passed the now sacred hill of Tepeyac, he heard the sound of birds singing, and when they ceased, he heard a woman summon him to the top of the hill. As he approached, a luminous woman who identified herself as the Virgin Mary and told him to go to the bishop and share her wish that he build a church at Tepeyac.

The bishop, however, did not believe Juan Diego, and asked him for proof. So when

Juan Diego saw the Virgin again at Tepeyac, she instructed him to go to the top of

the hill where he would find Spanish flowers that would not be available locally.

He picked them and hid them in his tunic. When he arrived at the bishop’s palace,

the bishop’s servants saw he was hiding flowers, but when they tried to take them,

they only saw painted flowers. Juan Diego eventually was allowed to see the bishop,

and when he arrived, he opened his cloak. The real flowers fell to the floor, and

an image of the Virgin was imprinted on the inside of his garment. The bishop instantly

believed Juan Diego’s story and made immediate plans for the building of a chapel

at Tepeyac (Poole, Stafford. Our Lady of Guadalupe : The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531-1797. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995. 27-29).

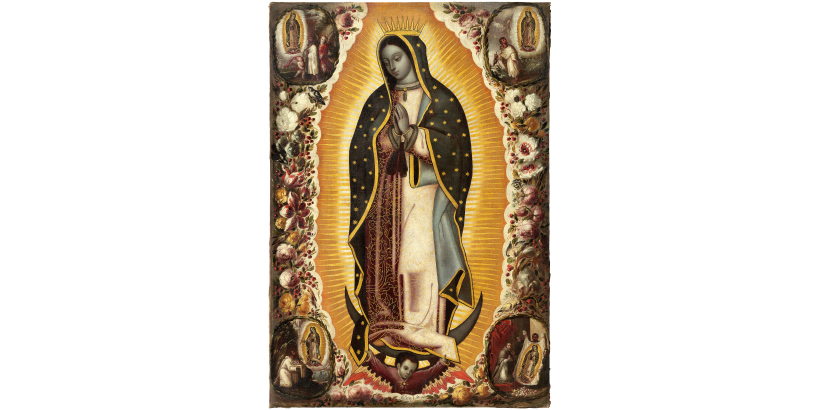

Beginning in the 17th century, we start to see a proliferation of prints and paintings

of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Above is Manuel de Arellano’s Virgin of Guadalupe, 1691. In the oil on canvas painting, which is part of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art collection, the crowned Mary is displayed in typical resplendent fashion, propped up by an angel.

Each of the four encounters with Juan Diego are represented in individual scenes in

the composition's four corners. Flowers adorn the border of the oval form created

by the emitting light from behind the Virgin.

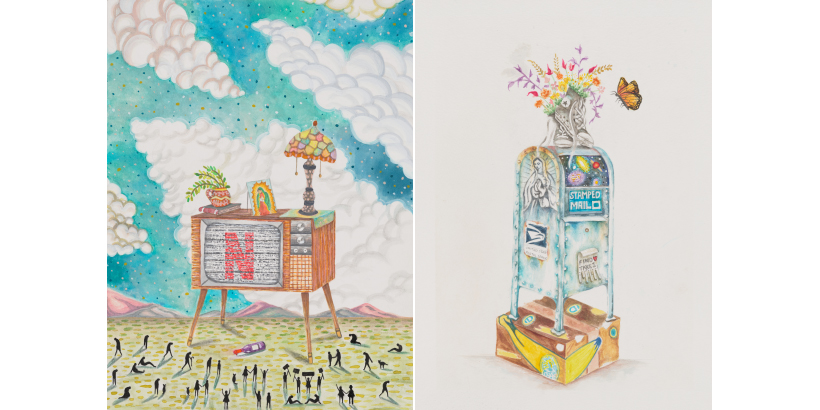

In two of Quintanilla’s works on view at Payson, we see the signature iconography

of the Virgin of Guadalupe – the robe, folded hands, and rays of light emitting from

behind. In Quarantine, 2021, a picture of the Virgin rests atop an old-fashioned tube-television. The TV

is powered on, revealing a staticky Netflix logo. Painted at the height of Covid,

the work represents how different people used their time during the pandemic. For

some, it was spent watching extraordinary amounts of streaming television. Others

used the extra time and solitude to reconnect with God, as denoted by the picture

of the Virgin of Guadalupe. At the bottom of the composition, silhouettes of people

surround the TV, suggesting that we’re all in this together.

Quintanilla’s Time Travel is Bananas, 2020, features a blue USPS mailbox. On the front by the letter slot, an image of

the cosmos greets would-be letter senders. Below that is a printed flier where an

interested person can tear off slits containing the pertinent contact information

on how to find love. On the side of the mailbox is the instantly recognizable imprint

of the Virgin of Guadalupe. I sense it’s a metaphor for the most important love in

the universe being that of God’s love, and I can’t help but think the flowers on top

of the mailbox allude to those picked by Juan Diego. As for the artwork’s title, when

we write letters, our thoughts on paper become frozen in time. Could this also be

a reflection of the timelessness of the Word of God?

The showcase of Quintanilla’s watercolors and drawings at Payson Library is the artist’s

first solo exhibition at an academic institution. The exhibition is on view through

May 5, 2024. To see more of Quintanilla’s work, visit his Instagram page, @artbyzurdo. For further reading, check out his interview with Shoutout LA.