"Wag-by-Wall" and a Wartime Christmas

Beatrix Potter is not someone who you would usually associate with Christmas. Her

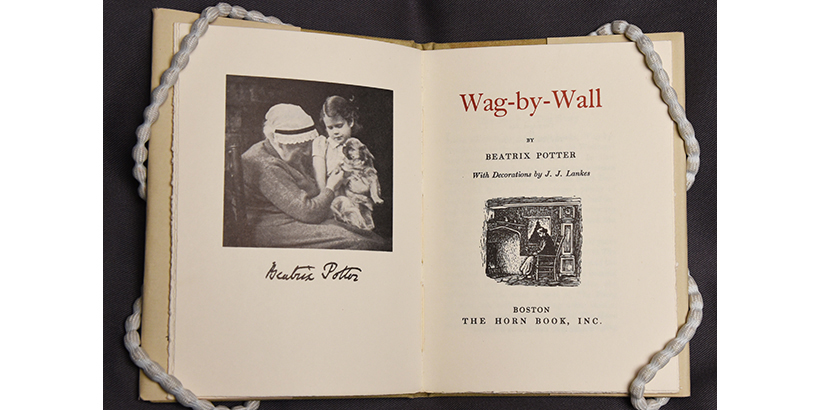

name conjures up beloved children’s classics like The Tale of Peter Rabbit or The Tale of Jemima Puddle Duck. But Potter is also the author of Wag-by-Wall, a little-known Christmas story published in 1944, a year after the author's death.

Pepperdine Libraries' Special Collections and Archives is the proud owner of a second-edition

printing from 1967. Like much of Potter’s writing, Wag-by-Wall features a cast of fantastical figures—a talking clock, a singing kettle—nestled

in the English countryside.

The story follows an impoverished farmer named Sally Benson. Despite the chattering

of her clock and the company of a friendly family of owls, Sally is lonely on Christmas

Eve. Even worse, she has received a letter brimming with bad news: Her granddaughter

has recently been orphaned, and money must be sent to pay for her transport to Sally’s

home in Westmorland. The penniless Sally is on the brink of despair when one of her

beloved owls comes down the chimney Santa-style with a stocking full of enough gold

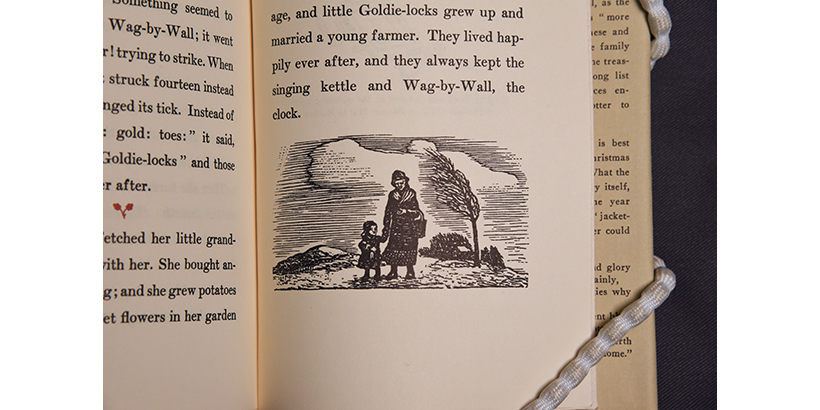

to cover any travel costs. In the story’s final scene, Sally and her granddaughter

are reunited.

Potter’s somber tale may strike us as far removed from familiar Christmas stories

featuring jolly snowmen or industrious elves. But Wag-by-Wall was published in the midst of World War II, when Christmas was a less-than-merry

affair for many. Even Wag-by-Wall’s illustrations—which, unlike those in Peter Rabbit or Jemima Puddle Duck, were not the product of Potter’s hand—seem to reflect a wartime austerity. The simple,

black-and-white woodcuts defy the cheery, color-saturated images we usually associate

with the Christmas season. Still, Potter does not leave her readers without hope.

Her message that families could be reunited even in the most improbable circumstances

would have resonated deeply with wartime readers. In Wag-by-Wall, Christmas remains a time for miracles.