Understanding J.R.R. Tolkien through a Christian Perspective

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.

“The Riddle of Strider,” from The Fellowship of the Ring

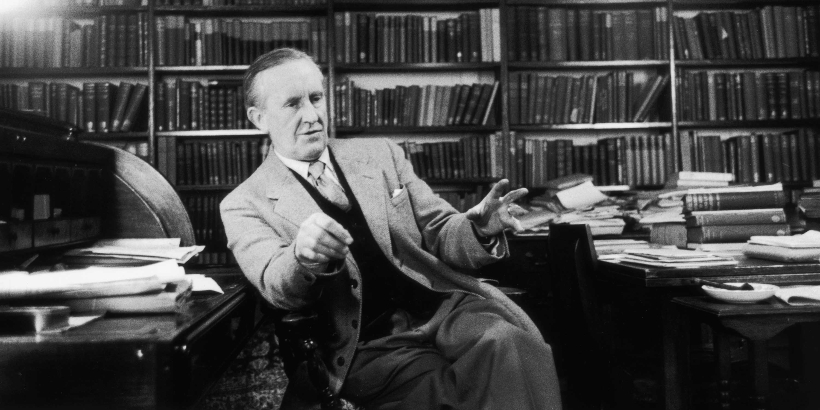

Pepperdine Libraries celebrates the 130th birthday of renowned British author and

self-proclaimed devout Catholic John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, born January 3, 1892. J.R.R.

Tolkien was a good friend of fellow Christian and Oxford professor C.S. Lewis, the subject of another blog post I recently authored.

Born in the Orange Free State in Southern Africa, Tolkien stayed there until he was three, before returning to King’s Heath near Birmingham with his mother, Mabel, and brother, Hilary. After their return to England, Tolkien’s father, Arthur, manager of the Bloemfontein branch of the Bank of Africa, died of rheumatic fever in 1896. Tolkien’s mother Mabel soon fell ill as well, dying of diabetes in November 1904. The orphaned Tolkien sons became wards of Father Francis Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory.

In school, Tolkien demonstrated an aptitude for languages and started learning Old and Middle English, Old Norse, and Gothic. After graduating with honors from Exeter College, Oxford in 1915 where he studied linguistics and philology, Tolkien joined the army, having been commissioned in the Lancashire Fusiliers infantry regiment. Shortly afterward in March 1916 Tolkien married Edith Bratt, whom he had met at the Birmingham Oratory as a child. By June 1916, Tolkien was in France to join the 11th battalion of the Fusiliers as a signals officer, where he took part in the battle of the Somme. Tolkien experienced traumatic loss and hardship during this time; one of his best friends from school was killed at the start of the battle, and another was killed in late 1916. By October, Tolkien had contracted trench fever and was sent back to England, where he remained in poor health for the remainder of the war. All told, four of his five best friends were killed in the war. As scholar Thomas W. Smith wrote, “In short, until he was twenty years old, Tolkien led a life of unrelenting loss, grief and suffering.”

After the war, Tolkien returned to Oxford where he participated in writing the New English Dictionary, and by 1920 he moved to the University of Leeds as reader in English language, eventually joining the faculty at Leeds as a professor in 1924. It was around this time that Tolkien began working on The Book of Lost Tales, which would be published posthumously as The Silmarillion in 1977. Following the publication of an article on early Middle English literature in 1929, and his groundbreaking 1936 lecture on the reassessment of Beowulf (“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”), Tolkien shared with the world his fiction for which he is most well-known.

Although The Hobbit, or There and Back Again would not see publication until 1937, Tolkien had started crafting literary worlds well before he had entered the war. As early as 1914 Tolkien was creating legends and languages (the rich details of which are far too complex to cover in this brief blog post) which would serve as the backdrop of Middle-earth in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Karl Kroeber wrote, “Tolkien is the only major fantasy writer to have created his fantasy world from a beginning in the systematic invention of languages. And he did this on the basis of a profound scholarly study of medieval northern European philology and literature.” The Hobbit started as a story for Tolkien’s children and was not considered for publication until publisher Sir Stanley Unwin reviewed a typescript. The book sold exceedingly well and Unwin asked Tolkien to write a sequel, which resulted in The Lord of the Rings, selling millions of copies and receiving enduring acclaim. Even after the widespread popular success of his works, Tolkien continued his academic career, holding the Merton chair of English language and literature at Oxford starting in 1945 until he retired in 1959. Tolkien published no further major works and died in November 1971. He is buried at Wolvercote cemetery outside Oxford.

While scholars may not find overt or allegorical references to Christianity in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote to a friend in 1953 that he viewed it as “a fundamentally religious

and Catholic work.” In a 1958 letter, he wrote, “There are a few basic facts [about

myself] which ... are really significant. I am a Christian (which can be deduced from

my stories) and in fact a Roman Catholic.” Scholar Thomas W. Smith reads Tolkien’s

religious vision in The Lord of the Rings as one of a Catholic imagination, partly through the lens of mediation. Smith writes,

“To see reality through the lens of mediation is to assent to the notion that God

is manifest everywhere and in everything. It is to believe that God's creative activity

is not something that happened a long time ago and then ceased.”

Pepperdine Libraries holds several works by J.R.R. Tolkien, including:

- Beowulf and the Critics

- The Hobbit: or, There and Back Again

- The Lord of the Rings

- The Silmarillion

- The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

- The Book of Lost Tales

- Narn i chîn Húrin: The Tale of the Children of Húrin

- Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary - Together with Sellic Spell

- The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays

Works cited and further reading:

"J. R. R. Tolkien." In Children's Literature Review, edited by Deborah J. Morad. Vol. 56. Gale, 2000. Gale Literature Resource Center (accessed January 13, 2022). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CQCXYD431176853/LitRC?u=pepp12906&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=c7c91c59.

"J. R. R. Tolkien." Gale Literature: Contemporary Authors, Gale, 2009. Gale Literature Resource Center, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/H1000099219/LitRC?u=pepp12906&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=fe67ffb. Accessed 12 Jan. 2022.

"J(ohn) R(onald) R(euel) Tolkien." In Contemporary Literary Criticism Select. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2008. Gale Literature Resource Center (accessed January 13, 2022). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/H1103470000/LitRC?u=pepp12906&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=637528b8.

Kroeber, Karl. "Tolkien, J. R. R. (1892-1973)." In British Writers, Supplement 2, edited by George Stade, 519-536. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1992. Gale Literature Resource Center (accessed January 13, 2022). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX1383900036/LitRC?u=pepp12906&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=b57d6142.

Shippey, T. A. “Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1892–1973), writer and philologist.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 12 Jan. 2022. https://www-oxforddnb-com.lib.pepperdine.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-31766.

Smith, Thomas W. “Tolkien’s Catholic Imagination: Mediation and Tradition.” Religion & Literature 38, no. 2 (2006): 73–100. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40062311.