From the Vault: Wordsworth’s Greek New Testament

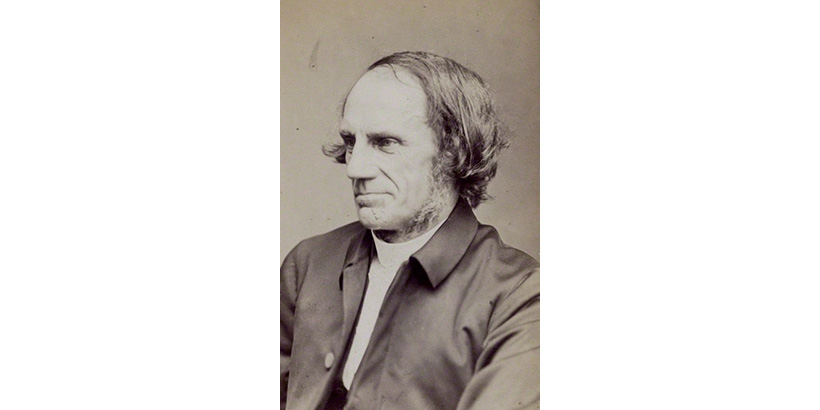

Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), doctor of divinity and Anglican Bishop of Lincoln,

penned many religious and literary tomes, including the memoirs of his uncle, the

celebrated poet, William Wordsworth. But it is his commentary on the Bible, The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, in the Original Greek with

Introductions and Notes, that is widely regarded as his magnum opus.1

Pepperdine professor emeritus of religion Randy Chesnutt recently visited the book in the Special Collections reading room at Payson Library. “I only recently became aware of this work, and I was pleased to learn that we have it in our library,” he confessed.

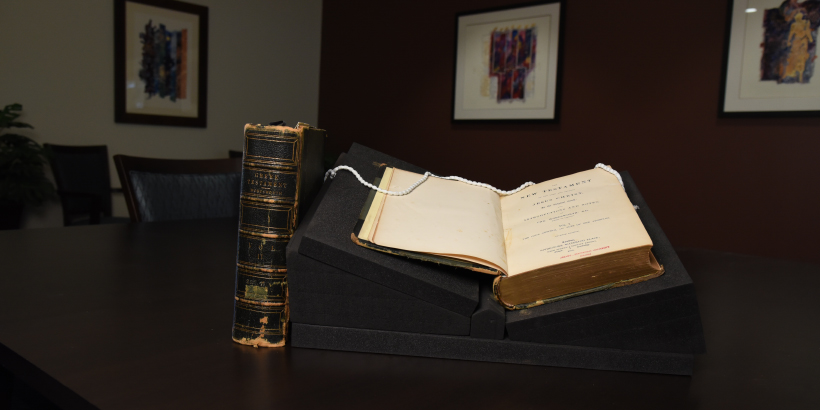

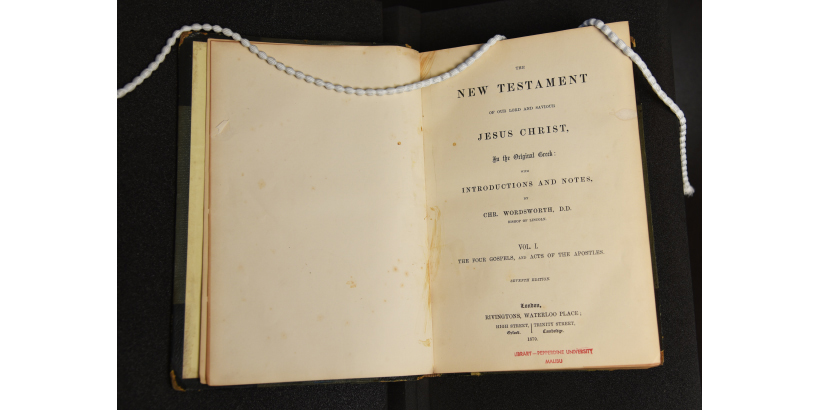

Special Collections and Archives holds the complete work of Wordsworth’s Greek New

Testament in two volumes. The complete commentary includes sections on the Four Gospels

& Acts of the Apostles, the Epistles of Paul arranged chronologically, the General

Epistles, and the Book of Revelation. The sections were released as they were completed,

from 1856 to 1860. The seventh edition, published in 1870 by Rivingtons in London,

is held in the university’s rare book collection.

Christopher Wordsworth’s early education was under Dr. Henry Dixon Gabell, a strict disciplinarian who had high expectations for accurate translation of the Greek text and no patience for blunders. Wordsworth writes, “I must say that though we feared Gabell, we loved him too…He taught us to love the Greek Testament as the ‘best of books,’ and used to give it as a ‘leaving book’ to pupils who had done their duty.”2 Such an influence produced “a most valuable habit of accuracy” and when Gabell left Winchester, Wordsworth says, “we were all deeply affected.”3 This early foundation in the classics and divinity produced “a great lover of books and of literature of all kinds.”4

What’s so special about Wordsworth’s commentary? According to the 1888 biography of

Wordsworth, Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln, 1807-1885, Wordsworth was “well-read beyond most men of his day” and well-versed in the writings

of the early church fathers.5 In his Greek New Testament, he assembles quotations from the likes of Origen, Ambrose,

Jerome, Augustine, and many others. Generally, he cites the church fathers “in full,

and not merely in reference” as he brings to bear their interpretations of biblical

passages.6 “This feature, the unprecedented (and still unmatched) compilation of patristic references

to New Testament passages, is more valuable than Wordsworth’s own notes. Wordsworth’s

notes sometimes seem a little naive or outdated to today’s scholars,” Chesnutt explained,

“The citation (and full quotation) of patristic references is the one enduring value

of this otherwise obsolete work.”

The early church fathers, including both Greek and Latin theologians and writers, worked in the Patristic Era, from the end of the apostolic period (early 2nd century) until the early Middle Ages.7 They played a significant role in establishing the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. Their preaching and writing shaped the core of traditional Christian theology.8 Because Wordsworth respected the wisdom of these early theologians, who were venerated by the church and who lived so near to the time of Christ, he included their quotations in his commentary. In this way, he called his readers to “elevate modern Exegesis to the standard of primitive Christianity, and to help…in recovering its ancient dignity” from the frightful trends of the day.9

Wordsworth held a high view of biblical criticism, regarding it “as a high and holy science.”10 He designed the commentary to be used by students in schools and colleges, and by candidates for holy orders.11 Wordsworth viewed the scripture as food for life and thought it his duty to supply it to his readers

…for the hallowing of their affections and for elevating their imaginations and for nourishing their piety and animating their devotion, and for enabling them to see and recognize with joy that Holy Scripture best interprets itself,… supplies the best discipline for the mind,...[and] satisfies all the aspirations of the soul.12

Wordsworth was explicit on the point that no one could rightly interpret the Holy Scripture without the aid of the Holy Spirit, by whom it was written, and only the Holy Spirit could prepare a person, morally and spiritually, to do so.13 However, he was steadfast in his view that the responsible interpreter of scripture should “bow reverently to the voice of the church,” saying, “The ancient fathers of the Primitive Church are the guides whom [one] will, above all, follow.”14

His biographers emphasize that “[t]he first thing that strikes [the reader of the commentary] is the extraordinary wealth of patristic learning with which [Wordsworth] fortifies his interpretations.”15 His acquaintance with the writings of the church fathers is evident and their spirit permeates his work.16 Some critics thought him unfamiliar with the more modern ideas of his day, but his biographers defend him on this point. “If he preferred to quote the older writers more frequently, it was because he thought ‘the old wine was best’, not because he had not tasted, or rather quaffed deeply, the new.”17

Students of biblical interpretation may especially value Wordsworth’s commentary in Greek, and his quotations from the church fathers, but those who value scripture as “discipline for the mind and satisfaction for the aspirations of the soul” may also be encouraged to learn of the work of Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln.18 Explaining his trip to Special Collections to view the book, Chesnutt admitted, “I know the book is available digitally, but I’m old school. I like to hold a book in my hands.”

If you, too, would like to hold the book in your hands, you may do so by emailing me to book an appointment in Special Collections.

Notes

1. John Henry Overton and Elizabeth Wordsworth, Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln, 1807-1885, (London: Rivingtons, 1888), 405.

2. Overton and Wordsworth, Christopher Wordsworth, 17.

3. Overton and Wordsworth, 17.

4. Overton and Wordsworth, 17.

5. Overton and Wordsworth, 400.

6. Overton and Wordsworth, 400.

7. Grossman, Maxine. "Church Fathers." In The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion, edited by Berlin, Adele. Oxford:Oxford University Press, 2011. https://www-oxfordreference-com.lib.pepperdine.edu/view/10.1093/acref/9780199730049.001.0001/acref-9780199730049-e-0684.

8. Grossman, Church Fathers.

9. Christopher Wordsworth, The New Testament of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, in the original Greek, (London: Rivingtons, 1870), xi.

10. Overton and Wordsworth, Christopher Wordsworth, 406.

11. Overton and Wordsworth, 407.

12. Overton and Wordsworth, 407.

13. Overton and Wordsworth, 407.

14. Overton and Wordsworth, 407.

15. Overton and Wordsworth, 412.

16. Overton and Wordsworth, 413.

17. Overton and Wordsworth, 414.

18. Overton and Wordsworth, 407.